I happened to spend some time reading and learning about Antonio Stradivari the famous violin maker from Italy. I enjoy connecting various subjects I read to investing and this post (and another one to be posted soon) is an outcome of this quirk.

"If I maybe so obnoxious as to say so - violin making is a king of an un-American activity. It goes against one of our fundamental beliefs, which is that things always get better and the new replaces the old - Progress."

- Sam Zygmuntowicz, one of the top violin-makers today

We live in a culture built on the unquestioned foundation that science and technology keep making things better. It is natural to believe that things and tools made today are unquestionably better than those made even in the recent past. In this context, it is astounding to observe that even in this age of movie-playing phones, AI and robotic manufacturing, the luthier (violin-maker) of today still strives to produce an instrument that would at least match something made 300 years ago!

A Stradivarius violin is considered the absolute gold-standard among violins. Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737) is supposed to have made around 1,100 violins over his life, of which around 650 are still in existence. The last Stradivarius was made in 1730s, when its maker Antonio Stradivari was in his 90s. A single Stradivarius sells for millions of dollars today and given a choice, most top violinists would unhesitatingly choose a Strad over other violins.

How is this possible? The world of violins has changed so much. How is it that a Stradvarius made centuries ago is still considered the epitome of craftsmanship and sound? What was Antonio Stradivari's secret? And what open secret about investing can be learnt from him?

Cradle of Cremona

Cremona is a city in Lombardy, Italy known for its violin making heritage. The history of violin making in the city began with Andrea Amati who moved to the city in the 1530s. He is credited with creating the modern form of the violin as we see today. Kick-started by the settling of the Amati family, there evolved a vibrant ecosystem of violin-making in Cremona. While Andrea's sons carried on the tradition of their father, the grandson Nicola Amati is considered as the first master violin maker who made the first great violins.

The power of apprenticeship

The system of education in those times was very different from the school system practised today. Today, we go to a school where we are taught a wide variety of siloed subjects. We are not taught how to meld these disparate subjects together to paint a unified understanding of the world.

This might not have worked for a craft like violin making. A violin maker should be able to synthesise knowledge of music, carpentry, physics and acoustics. He / she was not expected to learn everything, but specific buckets of knowledge in each subject that applied to his craft. Teaching was not in the form of theory - one learnt by observing the master intently and through direct practice over a long period of time. This observation and practice was repeated till a 'feel' for various aspects was developed. This is particularly important in violin making where the work begins with butchery (hacking the wood) and ends with surgery (in the end, even millimetres can make a difference between the right and the wrong sound).

The apprenticeship system evolved over thousands of years and was the primary mode of learning till a few hundred years ago. In those times, aspiring craftsperson apprenticed themselves to master craftsmen for many, many years (sometimes decades) before striking out on their own.

Antonio Stradivari is estimated to have joined the school of Nicola Amati as an apprentice when he was 12 to 14 years of age (around 1656) and is believed to have remained an apprentice till his master's death in 1680s. He was almost in his 40s when he struck out on his own.

Feedback loop

'For to the one who has, more will be given, and he will have an abundance.' Mathew 13:12

Stradivari was born in the right place (in or near Cremona) at the right time in history (in 1644, a century or so after the modern violin was born). He was born around the time violin was increasingly being accepted as an important music instrument by the most famous musicians of the day. It slowly became part of the royal orchestra. Legendary composers like Johann Sebastian Bach wrote solo violin pieces which proved immensely popular with the public at the time.

This acceptance was a major driving force in the maturation of violin making as an art. When violin was increasingly being accepted, more craftsmen began making the instrument, and as more craftsmen made the instrument, the craft itself improved through the sharing of ideas. Better violins were created which led to more musicians picking it up, which led to further musical pieces created specifically for the instrument for exposure to royalty and the public.

Cremona became the epicentre of its feedback loop. As far as violin-making was concerned, Cremona was a city that had and more was given, till there was an abundance. It was in the backdrop of this feedback loop in the history of violin that Antonio Stradivari pursued his craft.

In addition to the advantage of being in the right place at the right time, Stradivari was also blessed with extraordinary talent. During his apprenticeship, he is believed to have strictly followed the form and technique of his master Nicola. But by late 1680s and 1690s, he had begun introducing his signature innovations into violins. He experimented with the wood, with the length of the violins, the varnishes, among others. Violin makers today still try to emulate many of his ideas in their creations.

“What the pupil must learn, if he learns anything at all, is that the world will do most of the work for you, provided you cooperate with it by identifying how it really works and aligning with those realities.” Joseph Tussman

There have been a lot of theories and speculations to the reason for a Stradivarius' superiority - the wood available at the time, secret varnishes used, among others.

The most important reason is perhaps the most deceptively simple one - practice. Genius that he was, Stradivari was constrained by the traditions of violin making - the form, the wood, the techniques limited him; but paradoxically, he was utterly free to experiment and innovate within those boundaries. And that is what he did. Antonio Stradivari focused on a single craft (with all the constraints and the freedom) for around 80 years, working assiduously towards creating the perfect violin. He made more than a violin a month for around eight decades!

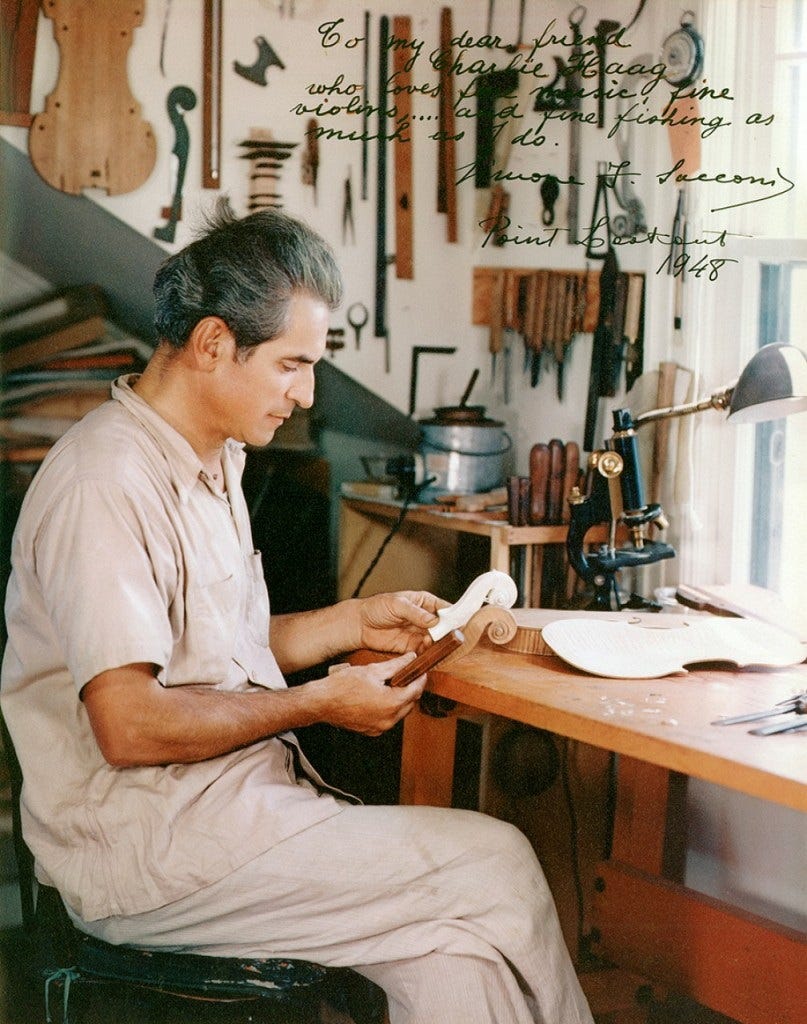

Simone Sacconi (1895-1974) was an expert Italian violin maker, teacher and restorer widely respected in the violin fraternity. He spent the last years of his life in Cremona researching Stradivari, preparing to write his definitive book on the maestro - 'The Secrets of Stradivari'. Simone wrote - 'This craftsmanship had become a myth because it was not understood. The simple truth of a daily routine of work and of the use of techniques which contained nothing mysterious.'

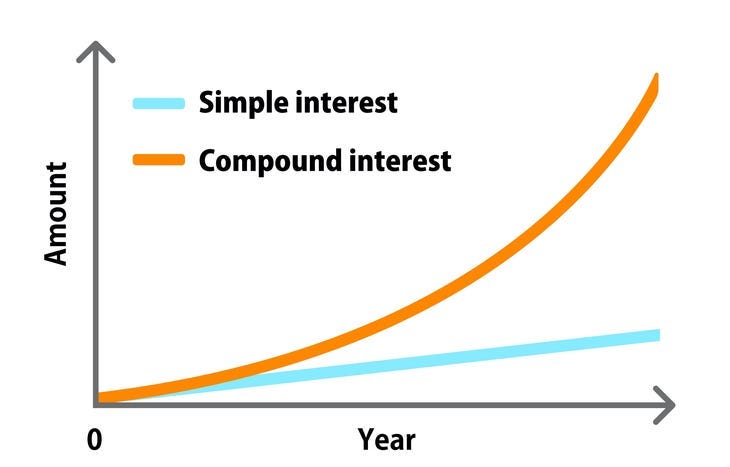

Our mind is not conditioned to understand non-linearities. We believe the world is a linear place with linear outcomes. Our mental make-up does not allow us to fathom the ungodly outcomes possible through compounding. Consistent efforts towards the same direction over a tremendously long period of time can produce incredibly non-linear outcomes. It is strange, but the power of compounding is perhaps overlooked because it is boring and simple. Where is the fun and excitement in focusing on one thing with discipline, and improving in that particular thing over a long period of time? There is no dopamine kick, there is no volatility - it seems dry and uninteresting.

Unless the thing / activity ignites the fire of passion. For Stradivari, it is clear that violin making was his passion, it was his life's calling, it sang to his soul. Why else would he labour over a craft, constantly finding ways to improve and innovate over seven to eight long decades? It is practice of a craft with the spirit of perseverance, focus and dedication that is the secret of the survival of a Stradivari violin.

One can see the business and investing world littered with Stradivarius equivalents - extraordinary outcome driven by a similar lollapalooza of factors, the foundation of all being compounding.

Take some of the strongest franchises today - Coca Cola, Berkshire Hathaway, Nestle, among many others. Each of these businesses are considered to be the epitome of success in their respective industries. But these outcomes are the result of steady compounding of their competitive advantages over a long period of time. Serving the customers, taking care of their employees and suppliers and strengthening their reputation a little bit every day, week, month, year and so on. The only way to build an extraordinary outcome - be it expertise or strength or competitive advantage is to have a small initial edge and then improve with discipline and dedication over a really, really long period of time. No mental model is as powerful as compounding.

One of my all-time favorite movies is 'Kung Fu Panda’, a movie that is pure legendary awesomeness. In the movie, a cute, fluffy panda named Po is anointed as the Dragon Warrior by the wise tortoise, Grand Master Oogway. Po's primary duty in the movie is to protect the secret of the Dragon Scroll (the reading and understanding which grants the reader super powers) from the evil snow leopard Tai Lung. In an attempt to win the battle, Po opens the dragon scroll and finds it to be empty. He is confused till a chance conversation with his adopted father, a goose (the reader would have realised by now that this is a really inclusive movie, all animals are represented) helps him understand the message of the scroll - There is no secret ingredient.

In a similar vein, there is no secret ingredient to the most outlandish achievements - all you need is a dollop of genius, a fountain of passion and a lifetime of discipline, all directed towards one single worthwhile goal.

Post-script

What do we really know? It is a really intriguing question. Most of the times, I think we know much less that we actually do. Sometimes there are beliefs that we have, things we feel absolutely certain of, but then you turn around and find out that the exact opposite thing could be the truth.

Here is a beautiful article written by Sean Iddings. In this article he argues that the value of a Stradivari is all in the mind! That there is no objective superiority to a Stradivarius. Yikes! What does that mean for the whole spiel on Stradivari that I waxed lyrical about.

I have been struggling to understand the quote above. What does it mean to have a brain that has two opposing ideas and is properly confused? Maybe it applies to the phenomenon of Stradivari - maybe both Sean’s article and my article are true; and maybe not.

Beautiful Rohith. Reminds me of the samurai sword makers.