Disclaimer: I am not invested in Rain Industries. I am not an investment advisor. I love thinking about investing and businesses, and this blog is just an expression of that love. I had written this article for the Intelligent Fanatics website and got permission from them to republish here.

This note was written in 2019. I have not updated the note for any developments in the business since I wrote the note. I still think this write-up is relevant for anyone interested in understanding the history of the company.

The reason I re-published the note in my blog is two-fold - 1) I remember enjoying writing the article and wanted it to be available online; 2) I intend to write a follow-up post purely to share some updated thoughts on the risks I perceive in the business structure.

Warning - The note is quite long. So long, that I would applaud anyone who reaches the end of it. (At this time, I could barely do that myself.)

The “Map is not the Territory” is a mental model with which I have some trouble. I am not sure I fully understand it yet. A map is nothing but a tool to understand and navigate the world better. For example, Graham, Buffett, Munger, Soros, Klarman, Druckenmiller etcetera have all shared their maps on how they navigate the investing world. But the problem arises when we apply the maps rigidly to reality. Maps are, by definition, sharply defined approximations of the incredibly messy real world. But sometimes the best way to understand a concept is through an example of a complex business- Rain Industries.

In fact, if like the ‘Evil Queen’ I ask the question: “Mirror, mirror on the wall; (of the businesses I worked on) which is the most complex of them all?”, the answer today would undoubtedly be Rain Industries. Rain Industries has been in the news quite regularly recently. Fascinated by what I read and curious to know more, I decided to spend some time to understand the company better.

This is by no means a recommendation to buy or sell the business. According to me, there are potential large risks that loom over the long term. This note details my limited understanding of a business that spans the globe, and the audacity of the reclusive entrepreneur who runs it.

Jagan Reddy Nellore graduated from Purdue University and received his initial training in the cement industry which was the family business. It struck me while writing this that I am a 30 year old guy (ok, almost 31 now) managing a small portfolio and writing articles for intelligentfanatics.com. At 30, back in 1996, Mr. Nellore was consumed with a far grander ambition. He was in the midst of setting up a calcining plant (which uses technology similar to the cement business) in Vizag; not just any calcining plant –the largest calcining plant in Asia.

Before we move further, let us understand calcining better. A calciner procures GPC (Green Petroleum Coke) and through ‘calcining’ (heating to remove impurities) manufactures CPC (Calcined Petroleum Coke). CPC is a key raw material (for anode production, which is a key material in the production of Aluminum) used in the manufacturing of aluminum, and forms around 5%-8% of the cost of production for Aluminum. Each ton of Aluminum requires around 400kg of CPC. Each ton of CPC requires around 1.3 tons of GPC.

Now, Aluminum production is quite energy intensive and the starting / stopping of a smelter is a time consuming and expensive process. This implies prompt availability is vital. The quality of CPC is extremely important, as low grade CPC would necessitate higher energy consumption.A lack of CPC would also keep a smelter idle. So CPC supply contracts with customers are generally long-term and it is not easy to displace an incumbent supplier. The quality of CPC is in turn dependent on the quality of GPC. GPC is a by-product produced during the refining of crude oil forming probably less than 2% of the refiner’s revenues. Thus a calciner is in the business of converting a waste by-product (which is more of a bother for refiners) into a pivotal raw material for its smelter customers.

However, the quality of GPC varies with the quality of the oil used in refining – low sulfur or sweet crude produces high quality or anode grade CPC. Refining of sour or high sulfur crude produces GPC which cannot be used for CPC production (but can be used as fuel). A refiner generally gets the highest realization for anode grade GPC as compared to ordinary GPC. So he is always incentivized to sell to a CPC player first rather than to someone who uses the GPC as fuel. Thus, the GPC contracts with refiners are also long-term in nature with high switching costs, given its low contribution to refiner’s revenues. Thus a calcining business enjoys considerable supplier and customer switching costs.

A calciner is basically a converter – he procures GPC and converts it into CPC. The economics are similar to those of any converter industry. On average a calciner makes a fixed EBITDA per ton and is not directly (but indirectly to some extent) affected by the price of Aluminum. The calciner’s economics depend on the amount of Aluminum produced by his customers. Generally, an increase or decrease in the price of GPC is passed on to the customers. The CPC and GPC prices are negotiated periodically (quarterly or half yearly) with regular pass-through.

Additionally, the process of calcining generates considerable heat, which can be used to produce electricity. While the initial capital costs to capture this electricity is high, the incremental operating costs of capturing such electricity and selling it is minimal, which makes it a high margin business once set up.

Coming back to Jagan Reddy Nellore, he obtained a grant of US$ 500,000 from the United States Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) for conducting the feasibility study for a calcination project in India. And he chose to set up a huge plant with 300,000 tons per annum (tpa) capacity. Calcining can be done through two processes – rotary and shaft. Mr. Nellore was implementing the rotary calcining which is economical only in large capacities.

The set-up of this facility offered glimpses of different facets of Jagan Reddy’s approach to business, a pattern if you will, that would be repeated in the decades to come:

Extraordinarily grand ambition: In what was probably his first independent entrepreneurial venture, he leased 42.5 acres of land and began setting up the largest calcination facility in Asia.

Focus on cost and quality: The scale and quality of technology would ensure cost competitiveness. He got in the best companies and contractors to set up the facility. For civil works, L&T was brought in, the EPC (Engineering Procurement and Construction) for the calcination plant was given to FL Smidth, and Sargent & Lundy was chosen as the EPC contractor for the power plant. The senior engineers and technicians were sent to some of the top calcining facilities in the USA to receive training before the plant was set-up. The plant was designed to be one of the lowest cost facilities in the world.

Affinity for debt and ability to arrange capital: The facility was funded through a number of sources. While Mr. Nellore and his family were the primary contributors of equity, he was able to bring in AIMCOR and Reliant Energy as co-promoters to the project. AIMCOR was to be the principal marketer of CPC for Rain while Reliant Energy was a technical advisor to the company. Debt was raised from a number of institutions – both domestic and international. By the time, the facility was finally set-up in FY2000, the company had equity of 80cr ($11.5 million) and a debt of ~300cr (~$45 million).

Integrity: In 1999, the Board of the Company decided to increase the remuneration of Jagan Nellore. But he declined the higher salary till such time Rain generated reasonable profits and continued to take his original salary of Rs. 39k per month (~$1000 per month). PwC was appointed as the auditor in 2001 at a time when the market cap was just 80cr ($20 million).

However, by the time the facility was set-up, the Aluminum industry was hit by the 2000 slowdown and given the complexity of the plant, the performance was affected due to technical reasons. The company had to restructure its loans to commence repayment of the loan from Oct 2000 instead of Oct 1999. But as conditions improved, the calcination business took off. However, they did face a few issues in the power segment. The power segment which contributed to more than one-third of the revenues faced regulatory issues due to repeated regulatory changes in Andhra Pradesh (the state where they sold power) which impacted them adversely. However the issue was manageable and this segment too contributed well to the profits.

The overall performance of the business was quite strong after the initial hiccup in 2000. Below is a consolidated cash flow statement of the company from 2000-2004.

As is evident, the cash flow generation was considerable which was used primarily to pay down debt. By 2004, the D/E which was ~4x had come down to <1.0x and the Company was in an extremely strong position. During the period the company continued to focus on cost reduction by tying up with TERI (a premium energy institute in India) and other organizations.

From 2003-2006 two major things happened.

Rain embarked on a capex plan to increase its capacity by a further 180,000 tons which would further cement its position as the largest player in Asia and would catapult it into the top 5 position in the world. This capex was completed in 2005.

AIMCOR, its marketing partner and co-promoter, was acquired by Oxbow Carbon which became the largest marketer of GPC and CPC in the world.

These two developments changed things. Overall, in the eyes of Jagan Reddy, there were two major risks which Rain faced- 1) despite being the 5th largest player in the world it was heavily dependent on Oxbow for procuring GPC and then selling CPC; 2) it generated considerable revenues from the Indian power sector which was over-exposed to volatile regulations. The risk of GPC in particular was particularly urgent as the availability of anode grade or high quality GPC was coming down in the world. As mentioned previously, low sulfur crude produced the best quality CPC. However, due to changing economics (differential in crude pricing), more refineries were refining high sulfur or sour crude which produced low quality coke that could not be used for calcining. The reducing supply of GPC at a time when he was looking to expand capacity could potentially become dangerous to the Company’s very existence. This dependence on a third party for both purchase of raw material and sale of finished goods did not make him comfortable.

The Battle for the Calcination Market

To rectify this situation, Mr. Nellore began scouting for acquisition candidates in the US, which then housed the largest CPC players in the world – Great Lakes Carbon (GLC) and CII Carbon. The US also had large supplies of high quality GPC- due to the presence of large deposits of low sulfur crude.

In Mar 2006, Rain, through a subsidiary in the USA acquired ~20% stake in GLC for an amount of $123.2 million (Canadian $11.99 per unit). GLC was the largest CPC player in the world with a capacity of 2.45 million tons and 23% global market share. It was a pioneer in the space and set up the first calcination plant in 1936. This acquisition was funded by debt and was to be a precursor to Rain’s attempt tobuy the entire business through an LBO. To put in context the audacity and ambition of Mr. Nellore, Rain then had a capacity of 480,000 tons.

In early 2007, Rain made an offer to buy the entire business at C$11.6 per unit. But at this juncture, Oxbow leapt into the fray and offered a higher price per unit to GLC. Rain increased its bid to C$13.25 per unit and subsequently to C$13.5 per unit as Oxobow continued to outbid Rain. Oxbow subsequently increased the bid to C$14 per unit.The price of C$14 was ~20% higher than the initial price offered by Rain. Mr. Nellore at that point of time decided to withdraw from the bidding process as he was not convinced about the value of the business for the price he had to pay.

The lucky upside to Rain was that it had paid C$123 million at C$11.99 per unit for a 20% stake, which it sold to Oxbow at C$14 per unit (Oxbow was forced to purchase as per the terms). Additionally, it also received a C$17 million termination fee as the deal was not consummated. Altogether, it made C$160 million on the initial investment of C$123 million within 18 months.

And three months after the GLC deal was cancelled, Rain announced the cash purchase of CII Carbon, which was the second largest player in the CPC industry, for a price of $595 million. CII Carbon had a capacity of 1.84 million tons which indicated a purchase price of $324per ton. Oxbow on the other hand paid more than $340 per ton.

In order to make the above acquisition, Mr. Nellore merged the calcining business (Rain Calcining) with his cement production business (Rain Cement). The company also had to issue equity to complete the acquisition. This was to ensure that the balance sheet could take the debt required.The debt was structured to be long-term and matured in 2015.

A debt funded acquisition of a company 3x your revenue and 3.5x your capacity during an upcycle is on average, a very bad idea. But one could say he had no choice. Immediately after the respective purchases, Rain initiated talks to sever relationships with Oxbow. Oxbow eventually sold its stake in Rain in the open market. It is a guess but probably it was the souring marketing relationship with Oxbow (which was Rain’s primary source of raw material supply and also assisted heavily in marketing its goods in various markets) that forced Mr. Nellore into this move. He had to buy a US player to ensure stable raw material availability which ensured long term sustainability of the business.

CII strengthened Rain’s business in many ways.

The Louisiana – Mississippi area, where CII has plants is one of world’s major sources of low sulfur crude oil which produced high quality GPC. This implied lower logistic costs and simultaneously higher quality raw material sources which is a major strength in a commodity industry. In fact, CII believed it could charge a premium for its CPC as compared to other suppliers, and due to its quality and raw material network enjoyed higher capacity utilizations.

CII also had strong relationships with refiners (GPC suppliers) and Aluminum customers going back decades in some cases. In fact, a couple of plants were co-located with refiners reducing transportation cost.

Due to regulatory reasons, no new CPC plant was allowed to be set up in the USA. This implied major barriers to entry in a region known to produce high quality raw material.

Importantly, it had a deep institutional knowledge in the calcining business that would prove pivotal. CII was a recognized technological leader and had published multiple papers on calcining. It also had a patented technology that allowed usage of alternative raw materials which are typically priced at a discount to traditional anode grade coke. This would evolve into a huge advantage as it would further reduce its cost of raw materials (thereby strengthening its position as low cost player)in an environment when anode grade GPC availability was reducing.

To run the CPC business, Mr. Nellore brought in Gerard Sweeney, the former board member of Rain and CEO of AIMCOR. Mr. Sweeney was a long timer in the international carbon industry and since 2000, as been instrumental in the global expansion of calcined petroleum coke production throughout Asia and the Middle East, especially China, India and Kuwait.

Aggression overdrive

In the year after the acquisition, the debt-equity of the business had gone from below 1.5x to above 4.5x post acquisition.

Despite this, buoyed by the acquisition and the performance of CII, Mr. Nellore, in Feb 2008, decided to launch a study to construct a CPC plant in China. The planned capacity for the new facility was between 300,000 and 500,000 MT/yr, with start up in early calendar 2010. The focus was on adding new facilities to increase capacity and reducing distribution costs for end consumers. Earlier, in FY07, there were also plans to set up additional capacity of 480,000 tons in India as well which were to start-up in 2009.

The cement industry was also doing well in India at that time due to the infrastructure boom, and Rain increased its capacity by 1.5 million tons per annum at a cost of 334 cr (~$65 million).

The promoters had also pledged a major portionof their own holdings in the company. This is even more worrying when one realizes that the cement plant (which was the original family business of the Nellore family) was in extremely bad shape in the beginning of the decade and required major debt restructuring coupled with an upturn in the cement cycle to come out safe.

Continuous intent to expand right after an LBO in an upcycle when your shares are pledged is the most dangerous combination there is.

Recession to the rescue; Smart Capital Allocation; Positioning to harness velocity

So basically, Rain’s business was dependent on oil refining industry (for GPC supply), and sold CPC to the Aluminum industry. It also sold cement in India. On top of the exposure to commodities on both ends of the spectrum, it had also done a huge debt funded acquisition just before the recession and pledged shares. What could go wrong?

Well, surprisingly (and maybe luckily) not much did go wrong. The consolidation resulting from the acquisitions by Oxbow and Rain, which were both major players in the global CPC market pre-acquisition, resulted in a more oligopolistic market. Also, as mentioned previously, the substantial debt funded acquisitions by Rain and Oxbow (debt/EBITDA of ~6x after acquisition) meant their balance sheets needed repair. And so when the recession hit, the pricing did not turn irrational. As mentioned previously, the CPC industry which is a converter continued to generate EBITDA per ton in a fixed range, but the range had moved upwards due to lesser price competition. As per Rain, the EBITDA per ton which had gone to $30 in the past now would range between $70 -$120 (an average EBITDA margin of above 20%) in the new scenario. In addition to the support from a healthier marketplace, Rain also benefitted from the disciplined approach of Jagan Nellore and Gerard Sweeney. Mr. Nellore was clear that the company would not chase volumes at the cost of profitability. There were repeated instances where the company produced less to ensure margins were protected.

The combination of both of the above factors led to strong cash generation through the recession. In fact, the company became stronger through the recession validating the strength of the CPC business. Mr. Nellore’s focus shifted from expansion and growth to internal strengthening. Below is a consolidated cash flow statement of the company from 2008-2012.

The capital allocation in the downcycle is quite interesting to observe. Rain generated free cash flows of 1,863 cr or $395 mio in the five years (remember the acquisition of CII was for $595 mio when the exchange rate was more favorable).

The free cash flow generated was used to strengthen the balance sheet, as the net debt to equity reduced from a peak of 4.2x to 0.9x by 2012 end. Mr. Nellore also rewarded the shareholders through dividends and buyback (when the share price crashed after the recession).

The focus on cost reduction and quality improvement continued through the period. The company came up with a proprietary technology to generate considerable cost savings which would further strengthen its low cost advantage. During this period it even shut down a CPC plant in the US as it would meet the management’s return criteria.

Debt refinancing and Organizational Restructuring

To fund the acquisition of CII, Mr. Nellore had to take high cost debt, with a major portion of the debt costing 10% and above. Also, almost the entire assets of the company were given as collateral for the debt – the major portion of which was maturing only in 2015. In 2010, the company entered into a complex restructuring process which resulted in the following –

It refinanced its higher cost debt with lower cost of 8% and lengthened the maturity from 2015 to 2018.

Organization restructuring done and for the new debt only the assets of the US entity (CII Carbon) was provided as collateral.

The Indian cement and calcining operations were kept as separate legal entities and were unencumbered. This ensured that the creditors had access only to the US calcining entity. Also, intent was to keep the cement business completely unlevered and use the cash flows generated for shareholder distributions – in the form of dividends or buybacks. While the calcining business was to house the debt and fund any further acquisitions in future.

As per Mr. Nellore, the structure also enhanced the flexibility as well as it allowed him to enter into strategic transactions (PE, acquisition, strategic sale) of any entity or list the US entity (if required) when the opportunity came. This structuring allowed him to maximize velocity by preparing rather than predicting.

By 2012, the business had revenues of almost $1 billion, profits of ~$90 million and had generated a FCF deficit only twice in its operating history. But Mr. Nellore was looking to derisk his business further. While Rain had a cement business, it was still heavily dependent on the Aluminum industry. And so after the restructuring in 2010, he remained on the lookout for a business to acquire – and he found one in Europe.

Rutgers– The Canvas is Complete (?)

In Oct 2012, Mr. Jagan Reddy Nellore stunned the world (again) with a successful $900 million purchase of Rutgers, a chemical business with plants in Europe and Canada, and an upcoming plant in Russia. At the time of acquisition, Rutgers had revenues of $1.1 billion and EBITDA of $147 million. The acquisition was (of course)funded with debt, which ballooned to more than $1 billion. But the debt was structured differently this time around – Rain raised $400 million worth in dollars and $270 million worth in euros with an average interest rate of less than 8.5%. This was to match the debt with the underlying cash flows which were primarily generated in US$ and Euros. Only the US CPC assets (that is the CII business) was used to raise the debt and the Indian calcining and cement businesses remained free.

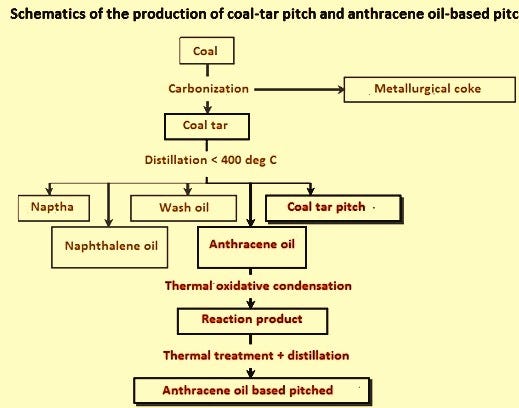

Now let’s (try to) understand the business of Rutgers. Rutgers procured coal tar from (blast furnace) steel manufacturers and distilled it to form coal tar pitch and other chemicals. Coal tar is a by-product of the blast furnace steel manufacturing process, and forms a very small portion of the steel player’s revenues. However, coal tar pitch -which is obtained by the distillation of coal tar - is an extremely essential ingredient in Aluminum production (each ton requires 100kg of coal tar pitch). The quality of coal tar pitch is extremely important in Aluminum production. Given the increasing popularity of electric furnace based steel production and reducing blast furnace capacity, the availability of raw material is on a long-term downtrend, and thus existing relationships are extremely important – and Rutgers had many of these. Also, Rutgers had a strong R&D team (15 patents and 24 trademarks) and had among the best plants in the world. The observant reader would have by now noticed the similarities in the coal tar pitch (CTP) and the CPC business. CTP too was a by-product converted into a valuable end-product in the Aluminum industry, where customer and supplier relationships were extremely important. The pricing structure was also similar to that in CPC, with a pass-through based on supply and demand, which meant like CPC, CTP also generated a healthy fixed EBITDA per ton.

Additionally, CTP had another major feature – coal tar and CTP both had to be transported in the hot liquid form in specialized containers as they solidified in the room temperature. Thus it was even more of a regional market than CPC (as it was difficult to be transported to long distances) and a strong distribution network was extremely important. And Rutgers had an extensive distribution network with deep sea ports, rail car terminals, specialized barges, etcetera.

But that is not the whole story. The distillation of coal tar produced not just coal tar pitch (48%) but also naphthalene oil (12%) and aromatic oils (40%). These other chemical oils could be further refined into a number of compounds like phthalic anhydride, naphthalene, resins, benzene, toluene, etcetera. At the time of the acquisition, majority of the chemical business was commoditized in nature(with prices linked crude oil or derivatives) but there were some portions like resins, modifiers and others which had specialized characteristics and Rugers had built strong brands in these.

The difference between Rutgers as compared to its peers was that it had among the most integrated operations. At the time of acquisition, it was the second largest distiller in the world after Koppers with a 1.1 million ton distillation capacity. Its plant in Germany was the single largest distillation plant in the world with a capacity of 500,000 tons. There were probably multiple reasons for the acquisition of Rutgers:

With the acquisition, Rain would become a single source supplier for all carbon needs for Aluminum industry. This would increase customer switching costs and enable better value for Rain as well.

Diversification – While initially Rain generated a significant portion of its revenues from the Aluminum industry, today it generates around 36%. The remaining is split between construction, automobiles, specialty chemicals, carbon black, wood treatment, graphite, coatings, etcetera.

A wider canvas- in the sense that the chemicals that were produced currently could be further processed into specialty applications.

Now, let us see how the story unfolds after the acquisition.

The aluminum industry went through an extremely painful period post 2012. Demand shrunk across the globe and the inventory levels were very high. The industry was in deep pain till the end of 2015 before it began bouncing back in 2016. The industry received a major shot in the arm due to the pollution curbs in China. China, which had a major share in the CPC and CTP global market, saw correction in capacity while the reduced inventory in the system due to three years of pain led to upward movement in the prices of CPC, and CTP which benefited Rain.

However, during the period of pain, Mr. Nellore and team were not idle. They continued to focus fanatically on improving quality, reducing costs, improving capability and enhancing capacity in high entry barrier segments. In fact, the company spent a noticeable amount on expansionary capex from 2012 to 2018, some of which are listed below:

Russian facility: In Feb 2016, the company completed a 300,000 ton state-of-the-art coal tar distillation facility in Russia which would supply to Rusal and also other Asian markets. This facility is perhaps the latest and technologically the most advanced one in the world. The products are sold in US$ or Euros and hence not exposed to rubles.

Flue gas desulphurization plant at a US CPC facility: This allowed it to process low quality raw material (GPC) to produce good quality CPC while reducing the emissions. It also allowed generation of energy which are sold to the government utilities at 60-70% margin (as mentioned previously, the operating cost to harness electricity is low).

Carbores (17,000 tons) and Phthalic anhydride plant set-up: In an effort to reduce the commodity portion of the chemical business, capacity expansion was done in these businesses which enjoyed assured offtake from customers and higher margins.Carbores was a brand owned by Rutgers and had 90% fewer toxic substances and opened up newer markets. Phthalic anhydride is an intermediate chemical used in manufacturing many other chemicals.

De-bottlenecking in Hamilton, Belgium, Germany and Russia (with minimal capex of <$20 million): With minimal capex, the capacity in Hamilton was increased by 10% or 23,000 tons. Also, in 2018, petro-tar de-bottlenecking (increasing capacity by 60,000 tons) was done in the European plants with the intent to leverage its raw material mix. This would allow the coal tar plants to distill petro-tar (which can be mixed with coal tar to be used in Aluminum plants) as well which would increase the flexibility and reduce cost (as petro-tar is more easily available).

Expansion of cement facility and setting up of waste heat recovery: With an intent to improve efficiency and reduce power consumption it invested 42cr (~$7 million) to upgrade the cement plant which also improved its capacity by 700,000 tons or 33%. They also set up 2 waste heat recovery plants of total capacity of 11.1 Mega Watt (MW). This would reduce pollution as well as costs, as the entire power would be for captive use (power costs are a major portion of costs for a cement plant).

Blending facility for CPC in India: Rain had most of its calcination capacities in the US which also had large supplies of GPC. But the long-term growth in the Aluminum industry was in the Asian regions. In order to optimally utilize its capacity in the USA (which was seeing declining demand due to closure of smelters in the Western markets) it leveraged its extensive and complex logistic capability to transport CPC produced in the US plants from low quality GPC (which would cost lower) to the Indian plants, where it would be mixed with high quality CPC and sold to its customers. This ensured high utilization across the system and the entire capex for this facility was just $2 million. Each additional ton of CPC sold would generate EBITDA $80-$120.

Shaft calcining and Hydrogenated hydrocarbon resins (HHCR): The latest capex of Rain is a $140 million ($70 million each) investment to set up a shaft calcining facility in India and an HHCR plant in Germany. Shaft calcining is a technology of CPC production which produces higher quality of CPC and is required by clients today. While HHCR would use the commodity output of the chemical business to produce specialty resins which enjoy margins of more than 20%. As per the company, this capacity would generate sales of more than $ 200 million. These capacities are expected to come on stream in 2019.

As can be observed, each major capital expenditure (capex) was either for reducing costs or improving capability or increasing capacity in a segment with reasonable barriers. And most of the capex were environment friendly (which is a key focus for the company today as we will see). In effect, all major capex done was to strengthen the company’s competitive positioning. Also, it is pertinent to note here that the focus was not just on expansion – there are a couple of instances where plants were shut down as they did not meet Mr. Nellore’s expected criteria of sustainable margins and returns.

Mr. Nellore and the management team were not just busy with expansion; they undertook an organizational restructuring of business as well. After the Rutgers acquisition, the company operated in silos with each country or region having its own specific teams. After a couple of years, the company underwent a restructuring where functional integration was carried to ensure that the entire carbon and chemical business globally acted as one company rather than multiple entities. This allowed them to generate efficiencies in logistics and allowed them to better serve their customers and grow their business. In 2018, there was another restructuring done at the product level where the Carbon and Chemical business were re-aligned to Carbon and Advanced Materials. The Carbon business already had a strong set of competitive advantages, and with the recent restructuring, the focus would shift to strengthening the chemical business. To strengthen the Advanced Materials business, Mr. Nellore brought in Mr. Ralf Meixner, a former long-time senior executive in BASF who spearheaded their battery materials business (primarily lithium ion batteries which are used in electric cars).

(Yet another) intelligent debt refinancing:

In 2017, the business underwent yet another debt restructuring. As mentioned previously, Rutgers was entirely acquired by leveraging the assets of CII in the USA. As part of the current debt restructuring, the entire Rutgers and CII business was given as collateral and debt was placed in different legal entities in the US and Europe. This was a more tax efficient structure as it would reduce the tax leakage in the debt free entities in Europe. The debt restructuring happened in two legs – in the first instance, the 8% debt maturing in 2018 was refinanced to a 7.25% loan maturing in 2025. The remaining 8.25% and 8.5% debt was refinanced into a LIBOR linked term loan maturing in 2025. The term loan had no pre-payment penalties, and the bond has call options for early next decade as well. With this restructuring, the average interest rate on the total debt reduced to a somewhere more than 5% as compared to more than 8% then, with the freedom to pay it down if they chose to do so.

And so, within one year, the company was able to reduce their interest costs by more than 20% while lengthening the tenor of the debt and at the same time reduce their tax leakage as well. At present, there is no major debt maturing till 2025.

Financials

I have tried to focus on key financial metrics in this section to best give a flavor of the company’s business. Rain today has cumulative sales of around $2 billion with the CPC business enjoying EBITDA margins of above 20% on average and the Rutgers business (when it was acquired) generated margins of more than 10%-12%. The Rutgers business was assimilated into Rain and while the numbers are not separately available, the margins there seem to have improved due to the measures discussed above.

The table captures the consolidated cash flow statement (interest paid is included in CFO calculation) from 2013 to 2017. The interesting point to note here is the cash flow generating strength of the business. Despite the 2013-2015 period being quite brutal, the cash flow generation remained positive even in those years. The cash flow generation was so strong that it could completely fund the high expansionary capex that the company implemented during this period and there was enough cash left over to pay reduce debt, pay dividends as well as conduct a small buyback.

This brings us to another key feature of Rain’s business model. As mentioned before, Rain’s carbon businesses (which form more than 70% of revenues) have converter characteristics. Any increase or decrease in finished goods or raw material prices are passed through to the customer or the supplier. Thus they make a broadly stable EBITDA per ton. In a rising price scenario, the finished prices tend on average to rise first, which leads to increased working capital requirements but higher EBITDA margins which implies the cash flow generation remains strong. In a weaker environment, the finished goods as well as the raw material prices come down. While the EBITDA margins decline they are broadly still reasonable but the working capital gets released due to the lower value of goods. Thus in general the company enjoys strong cash flow generation capabilities. And with the expansionary capex, the cash flows should only increase if everything else remains same (more on that later).

Now that we have established the cash flow generation capability of the business, we will turn to understanding the balance sheet and returns profile.

It is interesting to note that Rain has equity of ~$600 million while the goodwill (due to CII and Rutgers acquisition) is ~$800 million. This implies the net tangible equity is negative. Leverage maximizes returns on equity and Mr. Nellore has exploited this heavily by funding his assets with substantial debt of more than $1 billion with low cost debt (pre-tax cost of ~5%).

But it is not healthy over the long-term if the business earns high returns on equity only because of leverage. And so we turn to returns on capital. Returns on capital employed indicate the actual return generated by the business on the capital employed to run it. This number for Rain has been comfortably above 17-20% over the long-term even through the most difficult periods.

Characteristics of Jagan Reddy Nellore:

Mr. Nellore has been at the helm of Rain for more than two decades now and has a seemingly contrasting mix of characteristics.

He is Reclusive and Frugal: I could not find a picture of him online. Even the company website which has pictures of all top executives does not have a picture of him. He has never given TV interviews.From my understanding he is completely focused on running the business and is averse to publicity for the sake of it. As per a few articles online, he is frugal in his lifestyle and drives a hatchback in India. The salary he draws (Rs. 1.7cr in 2017) is a fraction of what his overseas employees and peers at much smaller companies would be drawing.

But Aggressive: While he may be a recluse in his personal life, his actions on the arena of business are anything but reclusive. In fact, I would say he has been extremely aggressive. There are not many other entrepreneurs in India who have done such large acquisitions (in relation to their size) and have structured their business as he has. The company’s market cap is less than $500 million while the debt on the balance sheet is more than $1 billion.

In some ways Conservative: The way the debt has been structured – at a low interest rate while keeping certain entities free of debt indicates conservatism. Rain also keeps substantial cash balances for interest payments. The year-end cash balance has ranged between 1.3x-2x of the cash interest paid the previous year on average,which has been maintained since the first major acquisition in 2007. After the 2008 recession, he reduced the pledged portion of shares and today not a single share is pledged.

Pro-cyclical at times: His quest for growth in the pre-recession period while the balance sheet was stretched was extremely risky. The CII acquisition, the cement capacity expansion was all done when the cycle was favorable. In 2014, he also decided on a solar JV on the excess available land; this was despite the pain he faced with the power segment in his calcination business in the past.

Transparent and Ethical: The statutory auditor of the Company is BSR & Co (Indian arm of KPMG) while the internal auditor is Ernst & Young. The company has had a stated policy of returning funds to shareholders (10%-15% of profits) since around 2010 which is way earlier than most businesses in India. Rain has also had concalls since 2008, from around the time it acquired the CII business. Apparently, the investor relations department has been instructed to speak to any and all investor however small he/she may be (I can vouch for that). While the disclosure levels were already quite good, they further improved, with the intent to better inform the investors.

Cash flow and returns focused: Mr. Nellore has been focused on cash flows and return right from the beginning andthis focus has percolated to the top management as well with the top executives speaking the same language. There have been multiple instances in the past when the company decided to reduce production to maintain profitability (when incremental volumes would not have been materially margin accretive). They have also closed down plants (both in calcining and Rutgers) that have not met their investment criteria.

Quality and cost focused: There is considerable focus on producing high quality products while simultaneously reducing costs. The annual reports and concalls talk about constant focus on R&D to use lower cost raw materials while maintaining quality. He also instituted a designation titled Chief Logistics Officer whose sole task is to manage the wide and complex logistics system of the company in order to improve efficiency and reduce costs. The logistics system of Rain is a major competitive advantage.

Ability to attract talent and inspire loyalty: Most of the top management has been with the company for more than a decade. For example, the President of the Carbon Business – Gerard Sweeney was the erstwhile CEO of Aimcor (the initial co-promoter of Rain) and a Board Member of Rain in the beginning of the century. When Mr. Nellore acquired CII, he was brought in to head the CPC business and was then subsequently made the head of the entire Carbon business (CPC, CTP, Creosote and Carbon Black Oil). The CFO, Mr. Rao, has been involved with the business for more than a decade. Most of the top management who came in with CII and Rutgers remain with Rain, and are at even higher positions today.

At the same time Mr. Nellore has not been averse to hiring outside talent. And he has been able to attract quality people to the organization. After the functional integration, he hired Dr. Gunther Weymans as the COO of Rain Carbon. Recently, after the re-alignment of the product portfolio, he has brought in Ralf Meixner as the Head of Advanced Materials.

Back to Map vs Terrain

Maps are tools to understand the world, but reality is ultimately quite messy and not that easily defined. The world is indeed covered with shades of grey. In case of Mr. Nellore, he has many characteristics of both an intelligent fanatic as well as an outsider capital allocator but does he fit them perfectly?

Mr. Nellore has guided Rain to become the largest CPC (13% of capacity and 30% of global production ex-China) and CTP (13% capacity and >25% production ex-China) player in the world.His focus on costs, integrity, quality, and technology coupled with his ability to inspire loyalty and attract quality talent indicate uncommon fanaticism. There is also a focus on rewarding shareholders. He is completely focused on running the business and indications are that no analyst can interact with him outside of concalls. But one would not be wrong in being worried by his aggression and eagerness to build scale. The pledging of shares and the extreme aggression in the last decade are particularly worrying. However, this decade has been considerably better on that front as not a single share is pledged. And then there are the potential risks in the business over the long term.

Applying Mr. Thondike’s Outsider model, Mr. Nellore is extremely private and reclusive (zero interviews given). He and his team seem highly focused on returns and cash flows. He has restructured his businesses to become more tax efficient, and has designed a highly efficient balance sheet that uses low cost debt to fund his high RoCE assets. But then there are his pro-cyclical tendencies, and one could also argue that he could probably have spent more on buybacks rather than certain expansionary capital expenditures. And maybe the balance sheet could be less efficient, meaning it could have lesser debt?

So, is Mr. Nellore an intelligent fanatic and an outsider capital allocator? My answer would be I don’t know.Maybe he both is and is not.

What do you think?

Haha. Thanks for your comment Madhav.

Your observations are relevant. Structurally, it does look like steel making and refining capacity is growing in Asia and not so much in the West. This is the major source of RM for Rain.

On your point on energy prices and others - it depends on if the problem is structural or cyclical. I am not sure if one can assume the European energy problem to be a structural one.

Also, on CPC, let us see how it plays out in the full cycle. Their plants in the US have the advantage in transportation costs as far as the Western markets are concerned.

But overall, you are right. Over the really long-term, businesses like these should shift to Asia. Given increasing production capacities coming up, and the fact that the West does not want to encourage such facilities - due to NIMBY effect.

But then the question arises - strategically, is that a good thing for them? Post Covid, would they want to lose strategic raw materials like Aluminium to Asia?

Hi Rohith, Great write-up it provides a good long term bird's eye view on Rain Industries. I have a few questions for the business. My basic question is with the overestimation of the strength of the CPC and CTP Business even though both are mission-critical for aluminum production but recently with high energy prices demand destruction took place in Europe (which is the region where CTP caters) and CTP margins went down and they closed the plant for some time period. Also with the CPC business which is their cash cow as of now suffers from a similar problem where lack of good quality RM supply along with a shifting of growth to Asia and Middle East which are dumping grounds for Chinese Companies which doesn't suffer same problems as they have a large steel and oil refining industry along with the largest coal base.

This seems more like a reverse of Pharma industry where the market is shifting from Regulated to Un-regulated markets.

Thanks again and sorry for long writeup. (Seems like your 2019 style of writing is rubbing off on me xD)